Indian Place Names

Several places in the Warrior Mountains and Tennessee Valley of northwest Alabama are known by their original American Indian names and are part of our local heritage. In the following, some of local Indian site names are identified as part of our historic and cultural landscape. Army officer Edmund Pendelton Gaines first recorded many of the original Indian locations during his survey of Gaines Trace from Melton's Bluff to Cotton Gin Port in December 1807 and January 1808. During this time, the territory he was surveying was Indian country and their claims had not been taken by treaty. Edmund was the brother of General George Strother Gaines, and he married Barbara Blount, the daughter of the Governor of Southwest Territory William Blount. In the early 1800's, the Southwest Territory was all the land south of the Ohio River and west of the Appalachian Mountains.

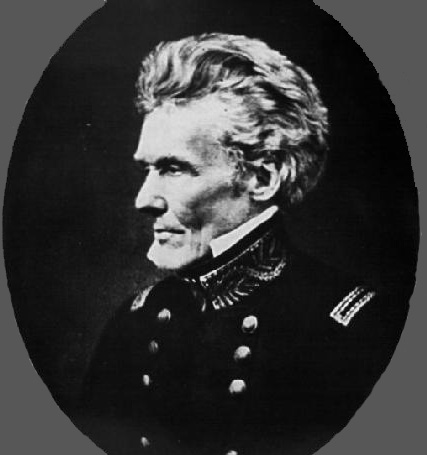

General Edmund Pendleton Gaines March 20, 1777-June 6, 1849

Alabama: Alabama, Muskogee for thicket clearers, was a member of the Creek Confederacy and originally called the Alibamos. Two sub-tribes the Creek people moved to the Big Thicket in east Texas around the 1780's and are known today as the Alabama-Coushatta. The Alabama lived at the junction of the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers in the State of Alabama. The Coushatta lived along the Tennessee River in north Alabama. The two tribes eventually united in east Texas, but were considered to related and members of the Creek Nation in the State of Alabama.

Big Head Spring: This large spring was located in the northern portion of Lawrence County, Alabama and was beginning of Spring Creek which is just north of present-day Courtland, Alabama. During the Wheeler Basin studies, an ancient Folsom point was found at the spring which was later flooded by the backwaters of Wheeler Lake. In addition, Mr. Rayford Hyatt found three Clovis points on an island adjacent to and north of the spring. The finds of paleo points indicate a long term occupation of the area in excess of 10,000 years.

Big Nance Creek: The creek that flows north through center of Lawrence County, Alabama and empties into the Tennessee River less than one-fourth mile west of Wheeler Dam was originally recorded as Path Killer's Creek by Captain Edmund Pendelton Gaines on December 27, 1807. The creek was later changed to Big Nance Creek after Doublehead's sister Nancy moved to Shoal Town and lived near the mouth of the creek.

Black Warriors' Path: This Indian trail became a post route known as Mitchell Trace after the building of Fort Mitchell in 1811 in Russell County, Alabama. The fort was named after Indian agent David Brady Mitchell and the route connected Fort Mitchell to Fort Hampton in Limestone County, Alabama. The route came from St. Augustine, Florida and followed the corridor of highway 280 just east of Birmingham, Alabama and crossed the Tennessee River near Melton's Bluff in Lawrence County, Alabama, through Columbia, Tennessee and then to the Big Lick or French Lick (Nashville). This was the route used by General John Coffee to destroy Black Warrior Town near the present-day Town of Sipsey. Black Warriors' Path was first recorded on Alabama maps by John Melish in 1813 and 1814.

Black Warrior Wildlife Management Area: This area is located in Lawrence and Winston Counties of north Alabama, and was named in honor of the Creek Chief Tuscaloosa, which is translated to mean Black Warrior. The forest was originally called the Black Warrior Forest, but later changed to honor a white politician. The management area is also in the upper drainage of the Warrior River.

Browns Creek: Three Browns Creeks flow through north Alabama: 1) Browns Creek near Guntersville, Alabama; 2) Browns Creek beginning at Lindsey Hall in Bankhead Forest and runs into Brushy Creek prior to entering Lewis Smith Lake; and 3), Browns Creek in the extreme southwestern corner of Bankhead National Forest near Rocky Plains in Walker County, Alabama. All these creeks are named in honor of the Brown Cherokee family.

Brown's Ferry: The ferry was in Lawrence County, Alabama at the crossing of the Brown's Ferry Road from Huntsville to Courtland, Alabama. There was also another Cherokee owned Brown's Ferry near Chattanooga, Tennessee. The north Alabama ferry was originally operated by the Cherokee family of John Brown and historically recorded as being used as early as November 1813 by local Cherokee Cuttyatoy. John Brown's daughter Patsy married Captain John D. Chisholm who acted as a attorney for Chickamauga Chief Doublehead who lived at Doublehead's Town at Brown's Ferry. Betsy, another daughter of John Brown, married a Cox and for a short period the ferry was called Cox's Ferry, but it later reverted back to Brown's Ferry.

Browns Spring: This spring was located about one-half mile west of the old Jasper Road near the Inmanfield Road in the north part of Winston County, Alabama and was at the site of the original Looney's Tavern. It was named after members of the Brown Cherokee Indian family and in the early days used as a gathering place for locals. The famous meeting concerning the Free State of Winston took place near Browns Spring at Looney's Tavern. Bill Looney, who led a group of Union soldiers, was also known as Black Fox and was thought to be a descendant of Chief Black Fox's daughter who married a Looney. In 1890, my great grandfather Sidney Walker was shot at Browns Spring and died three days later.

Buzzard Roost Spring: The spring, which is just west of the Town of Cherokee in Colbert County, Alabama, was near the home of Chickasaw Chief Levi Colbert-Itawamba Mingo. He contracted Kilpatrick Carter to build him a fine home at the site, but Carter fell in love with Levi's daughter and married her; therefore, Levi gave the home at Buzzard Roost to his daughter. Later Carter built his father-in-law Levi another house at Cotton Gin Port on the Tombigbee River. On a trip to Washington, Levi stopped at his daughter's house at Buzzard Roost Spring where he died.

Chake Thlocko: This was the crossings of the Tennessee River along the Muscle Shoals, and was translated as the Great Crossing Place or the Big Ford. Several Indian trails crossed the river at Chake Thlocko: Natchez Trace (Colbert's Ferry), Doublehead's Trace (Blue Water Ferry), Sipsie Trail (Lamb's Ferry), Black Warriors' Path (river crossing near Melton's Bluff), Browns Ferry Road (Browns Ferry), and Old Jasper Road (Rhodes Ferry).

Chickamauga: This was the name of the Indian confederacy that operated in north Alabama under the leadership of Chickamauga Chief Doublehead. The Chickamauga were made up of members of different tribes and included the Lower Cherokee, Upper Creek, Chickasaw, Shawnee, Delaware, and Yuchi.

Chickasaw Island: This island is in the Tennessee River south of Huntsville, Alabama and was recognized as Chickasaw land in the Chickasaw Boundary Treaty of January 10, 1786. The Cherokee actually forced the occupying Chickasaw from the area during the Battle of Chickasaw Old Fields in 1769.

Colbert County: The county is named in honor of the Chickasaw Colbert family. James Logan Colbert of Scots origin moved to the Chickasaw Nation during his youth with traders. He married three Chickasaw women and had two sons who became chiefs of the Chickasaw-George and Levi Colbert.

Colbert's Ferry: This was a government ferry established as part of a treaty with the Chickasaw of December 1801. Colbert's Ferry was mentioned by Captain Edmund P. Gaines while surveying Gaines Trace in his field notes on January 8, 1807, as follows, "The mouth of 20 Mile-Creek is about 45 miles from Colbert's Ferry..." Chickasaw George Colbert operated the ferry until his wife Tuskiahooto died in 1817. After her death, George Colbert moved near present-day Tupelo, Mississippi with his other wife Saleechie, sister of Tuskiahooto. Tuskiahooto and Saleechie were the daughters of Chickamauga Chief Doublehead; therefore, George was the double son-in-law of Doublehead. According to the 1834 treaty with the Chickasaw, George Colbert made sure his reserve at Colbert's Ferry extended 60 yards south of the old home place to include the grave of his wife Tuskiahooto.

Coldwater: This was an early Chickamauga Indian village also known Oka Kapassa located at the junction of Coldwater Creek with the Tennessee River near Tuscumbia, Alabama. The source of the creek was Big Spring in Tuscumbia. The Indian village was destroyed by General James Robertson from Nashville, Tennessee in 1787 during the Chickamauga War.

Coosa Path or Muscle Shoals Path: The Coosa Path or Muscle Shoals Path was a route from Ten Islands on the Coosa River to Dittos then to Tuscumbia Landing. The path was recorded by Captain Edmund Pendleton Gaines while surveying the Gaines Trace from Melton's Bluff in Lawrence County, Alabama to Cotton Gin Port, Mississippi. On the rainy day of December 29, 1807, Gaines wrote in his field notes "...cross Coosa Path, leading from the lower end of the Muscle Shoals to Coosa Town, Creek Nation, bearing about S. 26 degrees. E. 70 miles distance."

Doublehead's Resort: This Lawrence County, Alabama site is located near the mouth of Town Creek about one mile south of the Tennessee River and is named in honor of Chickamauga Chief Doublehead.

Doublehead's Trace: This route was originally an old Chickasaw trail that was called the Old Buffalo Trail that led to the buffalo hunting grounds on the Cumberland River. The trail was upgraded to a wagon road by Doublehead and the Cherokee. The route was 100 miles in length from the mouth of Blue Water Creek to the Town of Franklin near Nashville, Tennessee and was called Doublehead's Trace. The Cherokees actually built some 300 miles of wagon roads in their nation.

Doublehead's Spring: Two different springs in north Alabama were known as Doublehead Spring. One of the springs was located about two miles southwest of the Tennessee River at Doublehead's Village near Mhoontown north of the Town of Cherokee in Colbert County, Alabama. The Doublehead Spring in Colbert County is shown on the 1839 LaTourette map. The other spring was on the north bank of the Tennessee River in Shoal Town about 100 yards west of the mouth of Blue Water Creek in Lauderdale County, Alabama. The Doublehead Spring near Blue Water Creek was shown on the 1816 Peel and Sannoner map.

Fox's Creek: This creek begins on the northeast side of Lawrence County, Alabama and runs into the Tennessee River at the county lines of Morgan and Lawrence. The creek is named in honor of the Principal Chief Black Fox of the Cherokee Nation. Black Fox lived for a while near the site at a place known as Mouse Town or Moneetown. Later his son Black Fox II lived and operated a trading post at the junction of Black Warriors' Path and Brown's Ferry Road about two miles west of the ferry.

Gourd's Island: This island is now flooded by the backwaters of Wheeler Lake in the Tennessee River near the mouth of Elk River. The island was named in honor of The Gourd, a Cherokee soldier who fought with General Andrew Jackson at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in March 1814. Gourd also founded Gourd's Settlement near present-day Courtland, Alabama that was recorded by Captain Gaines on December 28, 1807, as follows, "8th mile...At 119 chs. Cross the path which leads from Shoal Town, eastwardly, to Gourd's Settlement, about 3 miles distance".

Gourd's Settlement: This Cherokee village was first recorded by Captain Edmund Pendelton Gaines on December 28, 1807, as being located near Path Killer's Creek close to the present-day Town of Courtland, Alabama. The settlement was at the junction of the South River Road and Sipsie Trail. The Gourd along with two of the Melton brothers signed a letter on August 15, 1816, complaining about the killing of three Cherokees by James Burleson's family. Gourd was also identified by Anne Newport Royall in her book, Letters from Alabama 1817 to 1822.

Gunter's Village: The Town of Guntersville was named after Gunter's Landing in Marshall County, Alabama. John Gunter, who was of Scots-Irish lineage, married a Cherokee woman by the name of Ghigoneli. The Gunter family ran a trading post, powder mill, and a ferry across the Tennessee River.

High Town Path: This route was some 1,000 miles in length and ran from Old Charles Town, South Carolina to Chickasaw Bluffs on the Mississippi River near Memphis, Tennessee. It is named in honor of the Indian village of High Town located near present-day Rome, Georgia. The trail through north Alabama primarily follows the Tennessee Divide that separates the waters of the Tennessee and the waters that flows toward Mobile.

Indian Tomb Hollow: This is the site of the Battle of Indian Tomb Hollow that was fought between the Creeks and the Chickasaws around 1780. The area was the burial site for those that were killed in the battle. The canyon is located in William B. Bankhead National Forest in Lawrence County, Alabama. Indian Tomb Hollow has been set aside by the United States Forest Service and is considered a Traditional Cultural Property to be protected for future generations.

Kattygisky Creek: The spelling for the creek was not exactly the same as Kattygisky, the Chickamauga chief that lived at Shoal Town near the mouth of the creek. Kattygisky and Doublehead were friends and worked together in establishing Shoal Town. The mouth of the small creek enters Town Creek from the west about a mile from the Tennessee River, and the creek is named in honor of the Cherokee named Kattygisky. The creek originates in the northeast corner of Colbert County, Alabama and flows east prior to running into Town Creek across from Doublehead Resort.

Melton's Bluff: This Cherokee town was named in honor of the Cherokee family of Irishman John Melton and his wife Ocuma, who was the sister of Doublehead. John and Ocuma had several half blood children that lived at Melton's Bluff on the south bank of the Tennessee River in present-day Lawrence County, Alabama. Some two years before John Melton died on June 7, 1815, he built a fine house on the north side of the river in Limestone County, Alabama below Fort Hampton. The Melton's Bluff site was located at Tennessee River miles 287-288. Captain Edmund P. Gaines started his survey of Gaines Trace on the south side of the river at Melton's Bluff on December 26, 1807.

Mhoontown: Doublehead's Spring and Doublehead's Village was located near here on the south side of the Tennessee River in Colbert County, Alabama. According to the 1839 LaTourette map, the spring and village site appears to be about two miles southwest of the river .

Mouse Town: This town was also known as Moneetown and was located at the mouth of Fox's Creek on the south side of the Tennessee River on the northern corner of Lawrence County and Morgan County line. The old town site was recorded historically in the late 1800's by Colonel James Edmund Saunders as Moneetown and by General Edward Burleson of Texas as Mouse Town. Mouse Town was at one time the home of Black Fox.

Natchez Trace: This was a government route authorized by the treaty with the Chickasaws in December 1801 and ran from Nashville, Tennessee to Natchez, Mississippi. The trace is named in honor of the Natchez Indians of Mississippi and runs through the northwest corner of Colbert County, Alabama.

Path Killer's Creek: This creek was first recorded as Path Killer's Creek on December 7, 1807, by Captain Edmund Pendelton Gaines. The creek was originally named in honor of Cherokee Chief Path Killer who was elected principal chief of the Cherokee Nation after the death of Black Fox. Path Killer served as chief from 1811 to 1826. The creek later became known as Big Nance Creek in Lawrence County, Alabama.

Shoal Town: This Cherokee village was first recorded by Captain Edmund Pendelton Gaines on December 28, 1807. The Cherokee town was located on Big Muscle Shoals some seven miles from its eastern end between Big Nance Creek, Town Creek, and Blue Water Creek. Big Muscle Shoals was some 15 miles in length. In 1793, the Creeks said that Doublehead and Kattygisky had established the village. Doublehead's sister Nancy and his great nephew Tahlontuskee Benge lived at Shoal Town. About 1802, Doublehead moved from Doublehead's Town at Browns Ferry to Shoal Town where he had a trading post at the mouth of Blue Water Creek. He was living at Shoal Town when he was assassinated on Hiwassee River in Tennessee on August 9,1807.

Sipsey: The river that flows into Lewis Smith Lake out of the William B. Bankhead National Forest portion of the Warrior Mountains is known by the Indian name Sipsey which means poplar tree or some say cottonwood tree. The Sipsey Wilderness Area was established in 1975 and will be preserved and protected for future generations to enjoy.

Tennessee River: The river was originally called the Hogohegee or River of the Cherokees. The Cherokees controlled the vast territory that made up most of the drainage of the Tennessee River.

Town Creek: This creek was originally called Shoal Town Creek, because the Cherokee village of Shoal Town was located at the mouth of the creek and up the creek for some distance. Shoal was finally dropped and the creek became known as simply Town Creek. The creek actually follows the boundary of the present-day counties of Colbert and Lawrence of north Alabama prior to entering the Tennessee River.

Town of Cherokee: The Cherokees established a village near the town in the late 1700's even though it was part of the Chickasaw Nation. George Colbert stated that the Cherokees were living in the Chickasaw territory by his permission.

Tuscaloosa: This Creek Indian village was actually the second Black Warrior Town, with the first located at the mouth of Sipsey River and the Mulberry Fork of the Warrior River and known today as Sipsey. Both towns were named in honor of the great Creek Chief Tuscaloosa. Tusca is the Creek word for warrior and loosa is the Creek word for black; thus, Tuscaloosa means Black Warrior.

Tuscumbia: This town is named from the Muskogee words "tusc" meaning warrior, and "umbia" meaning one who kills; therefore, Tuscumbia means "warrior who kills"! Chickasaw Chief Tuscumbia was the namesake of the city.

Warhatchie: The younger brother of Doublehead was Warhatchie, and the community in Lauderdale County, Alabama known by the same name is probably in his honor.

Warrior Mountains: These mountains are the northern drainage of the Warrior River which was originally known as the Tuscaloosa River or Black Warrior River. The river is named in honor of the Creek Chief Tuscaloosa and the Creek Indian warriors.