Wildlife Lost from Warrior Mountains

Brown’s Spring is approximately 1/4 mile west of the Old Looney’s Tavern Historic marker on highway 41 in Winston County. It was at the spring in the fall of 1890 that the brisk October air was chilled from an early morning frost. The spring was flowing with fresh cool water capable of satisfying the thirst of both the hunters and their dogs. Excitement was in the air as the hunting party gathered at the spring to organize their day in the woods to obtain meat for their families. Sidney Walker, my great grandfather, was standing with other members of the party and talking about the day’s hunt. The stock of his rabbit-eared muzzle loading shotgun was resting on the ground with him leaning against it for support. One of the big bear and deer hounds stood up against my granddad for a pat on the head. As the big dog dropped back to the ground, one foot caught the rabbit-ear hammer causing the shotgun to discharge into my grandfather’s stomach and chest. Sidney died shortly after the accident. He never knew the big game animals he longed to hunt would disappear from the Warrior Mountains within a few years.

This true account is a sad beginning to a story about the demise and disappearance of large game animals, beautiful birds, and majestic trees that once were a vital part of the primeval wilderness of the Warrior Mountains of north Alabama. Hunting parties, an important part of wilderness life, provided a means of obtaining meat for hungry families, hides and furs which could be traded for goods, and the thrill of the hunt along with the fellowship of friends and neighbors. However, unregulated hunting practices began taking their toll on the native wildlife. Between the 1800's and early 1900's, several big game species were eliminated from the Warrior Mountains by “over hunting”. This tragedy is believed to have eliminated wildlife such as the eastern buffalo, eastern elk, black bear, timber wolf, and the eastern cougar.

Whitetail Deer-The deer were not completely eliminated, but their numbers were so low that the conservation department decided to restock the area. After the last original Warrior Mountains whitetail deer were drastically reduced from the forest, this herd was restocked with a northern subspecies of deer from Iron Mountain, Michigan during the 1920’s. Again in the 1990’s, deer from South Alabama were restocked in the Black Warrior Wildlife Management Area.

Mr. Rayford Hyatt, past conversation officer of Bankhead, relates an interesting story about the last native deer to be killed in the forest. According to Mr. Hyatt, the last pure blood line deer was a small racked buck that was hunted for two or three days by hunting parties before it was eventually killed. The deer was killed by James M. Flanagin on Hagood Creek in early 1909. Mr. Amos Spillers, one of the first conversation officers of Bankhead Forest, had the antlers of the last known native Bankhead whitetail deer. Many people came to view the antlers of this beloved wildlife creature which was once taken for granted by many in the forest.

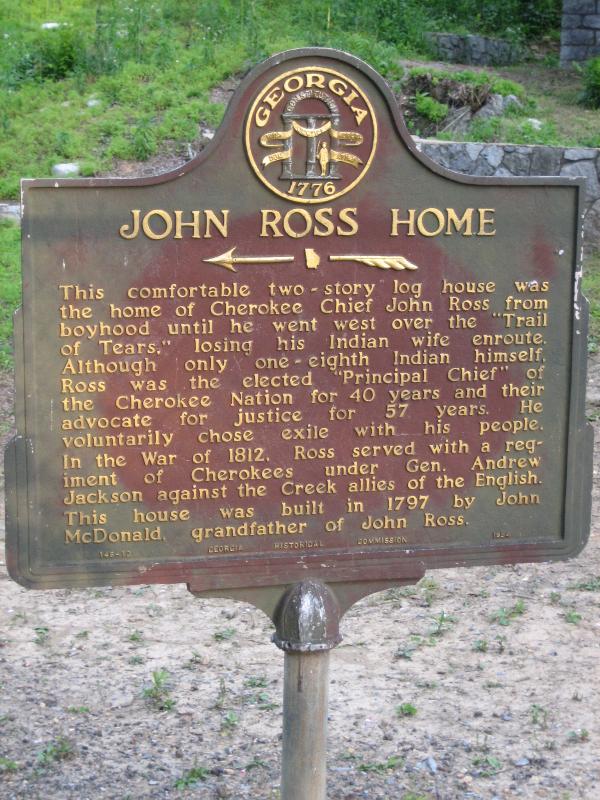

Timber Wolf-According to Mr. Hyatt, the last known timber wolf of the Warrior Mountains was killed during snowy weather in the Hurricane Creek area in 1910 by William Straud Riddle. William Straud Riddle, the son of Jonson (Rake) Riddle and Martha, was at least ¾ Cherokee Indian. His father was a full blood and his mother was ½ Cherokee. The wolf had killed several sheep owned by a Mr. Sewell who resided south of Grayson. After hunting and tracking the wolf in the snow nearly all day, the hunt ended without success. As Mr. Riddle started home toward the western side of Sipsey River, he found fresh wolf tracks in the snow. After tracking the animal a short distance, he saw the wolf standing next to a huge hollow log where it had a den. Once the wolf was shot and killed, it was taken home and placed in a standing position before it became stiff. After eating several sheep, the wolf was huge and weighed some 150 pounds. Many people came to see the carcass before it was finally discarded.

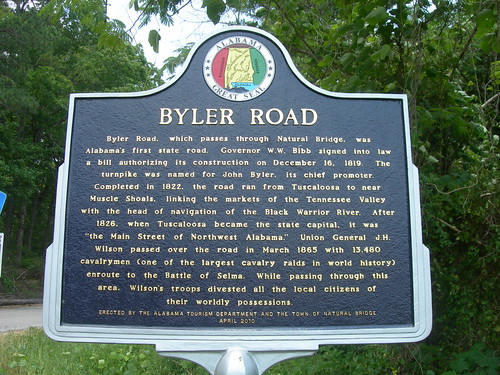

In the early days of Franklin and Lawrence Counties, wolf scalps could be used in the payment of taxes. Notice in the following law:

ACTS OF ALABAMA 1835 SESSION. ACT NO. 123 Pages 119,120

“After passage of this Act, it shall be lawful for Tax Collectors of Franklin and Lawrence Counties to receive all wolf scalps in payment of any county tax due from any person in the county, on prior affidavit made before an acting Justice of the Peace that the wolves were killed in Franklin or Lawrence County, as the case may be – Scalps received at the following rate; all scalps under one year $1.00; all scalps one year and upward $1.50; Tax Collector of each county to return affidavits with scalps to the County Treasurer as money for any county tax due from them as tax collectors – no money to be paid out for scalps; only receive scalps in payment of taxes.”

Three species of wolves were known to exist in the Warrior Mountains; grey (timber), black, and red wolves. This last known black wolf was shot in 1917 and is now considered extinct. The red wolf is recovering from the verge of extinction with one small pack re-established in Cades Cove of the Smokey Mountains National Park. The timber or grey wolf is found only in the northern portion of the United States.

Black Bear-The black bear was were eliminated from the Warrior Mountains as a breeding population in the early 1900’s. Specific information about the demise of the last black bear is unknown; however, many mountaineers tell stories of encounters their grandparents had with bears during the early 1800’s. Black bears loved corn and would attack the corn fields when the corn was in the roasting ear stage. Be sure to read about Dave and the black bear and Nancy and the bear cub in my Warrior Mountains folklore book. Nancy nursed a small cub until it got so big it would tear her clothes. Another interesting story is about Jacob Pruitt on his horse chasing a bear when he was thrown from his horse and killed by the black bear. Reports of bears still persist to this very day, but no known population of either in the Warrior Mountains. Black bears are still found in Tennessee, Florida, and the swamps of extreme south Alabama.

Eastern Cougar-The eastern cougar was known locally as the "painter or black panther" and struck fear in the early settlers of the Warrior Mountains of north Alabama. In the book Warrior Mountains Folklore, older people remember their grandparents talking about panthers. It is estimated that some 30 wild eastern panthers still roam the swamps of Florida and rank as the most endangered animal in the Southeastern United States.

Elk-The eastern elk migrated along the Appalachian and Cumberland Mountains in Alabama and Tennessee in the early 1800’s. The elk were rapidly eliminated by Indian and early settler hunters. The eastern elk were killed out in the state of Tennessee by 1870. No known record exists on the demise of eastern elk in the Warrior Mountains of Lawrence County.

Eastern Bison or Buffalo-The eastern bison or buffalo ranged from the Great Lakes into Florida. The eastern buffalo was much larger than the western buffalo was very black. By the late 1700's all the eastern bison were killed out of the Warrior Mountains. A major factor for the Chickamauga War carried out under the leadership of Dragging Canoe and Doublehead was the loss of their sacred buffalo hunting grounds. Dragging Canoe said, "The Buffalo are our cattle". The last known eastern bison were killed out in the southeast by the 1820's.

Passenger Pigeon-Passenger pigeons were beautiful birds that once filled the skies and woodlands of the Warrior Mountains. Old-timers have passed down stories of passengers pigeons. The birds were extremely abundant and flocks containing thousands of birds roosted in mature hardwoods. The passenger pigeons, much larger but similar to an oversize mourning dove, would use the same roost for years. One such roost existing in the northern portion of Bankhead was near the forks of Thompson and West Flint Creeks, and also on Sipsey River. Other places in surrounding areas immortalized the name of the passenger pigeon by being named “Pigeon Roost.” The pigeons were smoked out at night while on the roost by huge bond fires. They were also shot and killed at their nesting sites. Eventually, this beautiful wilderness bird was eliminated from Warrior Mountains with the last verified flock appearance in Alabama in 1893. Eight of these birds were killed before this flock of some three hundred birds flew away never to return to our state. The last known passenger pigeon died while in captivity on September 1, 1914, at the Cincinnati Zoological Garden. This wilderness bird that once fed on the giant chestnut, oak, beech in Warrior Mountains is now extinct.

Ivory-billed Woodpecker-The ivory-billed woodpecker, another large bird once native to the Warrior Mountains, is on the verge of extinction due to habitat destruction as well as needless killings. The last known ivory-billed woodpecker in Alabama died about 1906. The bird met its fate at the hands of a hunter who probably never considered his kill would be the last of the species reported from our state.

The ivory-billed woodpecker’s form was mystic and immortalized by prehistoric Alabama Indians who engraved its image on stone plates, handles of axes, and other ornaments of the Mississippian culture. If our modern ancestors had cared that much for this bird of mystery, our children today might have been blest not only by sight of the bird but also by the sound of its hammering beak in the hills and hollows of the Warrior Mountains.

Carolina Parakeet-The Carolina Parakeet was probably the most colorful and beautiful bird to inhibit our Warrior Mountains. In early 1819, Anne Royalle describes flocks of the birds in Lawrence County with their beautiful green and yellow plumage. The fatal flaw of the Carolina Parakeet was their love for ripening fruit and corn. When one bird was wounded, the others would hover to help. This endeavor caused the whole flock to become easy prey. Eventually, the Carolina Parakeet was totally wiped out, never to be seen again in the Warrior Mountains. The Carolina Parakeet is now extinct.

American Chestnut-The American Chestnut, the largest nut producing tree in North America, was once abundant in the Warrior Mountains. It is now sometimes found as only a small sapling or tree struggling for survival. With some documented to be 13 feet in diameter, these giant nut producers once claimed, if in a pure stand, millions of acres of timber land in the eastern United States.

In about 1910, Chinese Chestnuts, which carried the deadly chestnut blight, were imported into New York. The mistake proved to be very costly. By the late 1930’s, the blight had spread like wild fire down the eastern coast killing all the American Chestnuts in its path. Chestnuts of the Warrior Mountains also fell victim to the terrible blight. The Indians, early settlers, and wildlife of Bankhead once utilized the bountiful production of nuts from the majestic chestnut. Today, the American chestnut survives as a frail sprout in the Warrior Mountains.

Conclusion-Now over 110 years since the death of an early hunter of the Warrior Mountains in 1890, we look back with grief and sadness at the devastation wreaked upon our beautiful forest and its wildlife. But as the mighty American Chestnut reduced to its frail existence as a lowly shrub returns year and year from sprouts of the life giving stump again to claim its glory, new ecology warriors will arise to fight for the protection of our beloved land known as the Warrior Mountains.